game review: norco

20220404

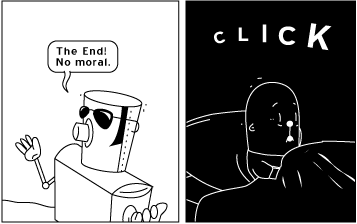

“pushes the boundaries.”

in 1988, konami released snatcher, written and directed by hideo kojima. snatcher was a curious game, both in its era and now. graphic adventure games had made their way to japan from the US with the portopia serial murder case. snatcher was an evolutionary step towards the adventure game’s most uniquely japanese form: the visual novel. snatcher featured very limited action gameplay, restricted to a handful of shooting segments. snatcher also didn’t feature the kind of puzzle gameplay expected of graphic adventure games of the time. there were no inventory puzzles, no complex chains of logic to deduce. instead, most of snatcher’s gameplay revolved around having conversations with people.

four years later, in 1992, chunsoft would release 「弟切草」, a game which finally realized that neither the portopia serial murder case’s pixel-hunting nor snatcher’s half-hearted action segments were necessary to create a compelling narrative video game. 弟切草 was arguably the first ever visual novel. chunsoft marketed it as a “sound novel,” a term that they would continue to use for such titles as 1998’s 「町」 and 2008’s 428: shibuya scramble. it featured occasional simple choices, and accompanied the text with graphics and sound to enhance the experience of reading.

the visual novel exploded as a genre, becoming the dominant form of japanese graphic adventure game in the 2000s. years before western adventure games like kentucky route zero realized that puzzles were actually obstructions to telling a compelling story in a video game, japanese game designers were able to achieve tremendous critical and commercial success with video games that featured almost no “gameplay” at all. no tedious puzzles, no quick time events, no action setpieces, no rooms full of freaks to turn into trash at the push of a button.

in 2022, we have norco, a game which is still stuck on snatcher.

i don’t mean this as too harsh of a criticism. norco, like snatcher, is still a fantastic game. i enjoyed my five hours with it. before playing norco, i saw many people comparing it to kentucky route zero, and my friends, let me tell you: norco is nowhere close to kentucky route zero. this, too, is not a harsh criticism: to fail to match the quality of one of the greatest video games of all time is not damning in the slightest. to praise norco as effusively as i think it deserves to be: it blows snatcher clean out of the water.

norco is a cyberpunk point and click adventure game set in the titular town of norco, louisiana. norco is a real town, the real hometown of the game’s writer and artist. in 1911, shell purchased the land the town sits on, and the name of the town became NORCO: the new orleans refining company. norco, the video game, takes place in a far-off cyberpunk future. replacing shell is shield, who operate a massive, mysterious oil refining facility full of robots in the center of town. you play as kay, a woman who grew up in norco but left many years ago to head west. she’s returned home now that her mother has died of cancer. upon returning home, she discovers that her brother, blake, is missing. kay joins forces with her mother’s rogue security robot, million, to search for him.

meanwhile, we occasionally cut back in time to kay’s mother catherine’s perspective, shortly before her death. she was attempting to earn some cash before she died by using a mysterious cryptocurrency gig economy app called quackjob. her sections of the game take place in and around new orleans. after getting her brain uploaded at a clinic, she meets up with dallas, another man doing work for quackjob. together they head to a warehouse and meet superduck, a powerful artificial intelligence which tasks them with retrieving a mysterious object that has fallen into the hands of a syncretistic christian cult of edgelord teenage boys.

this is where i say that norco is in the running for the funniest video game i will play all year. the reactions i witnessed to it on twitter compared it frequently to kentucky route zero, but much of the game’s tone is much closer to night in the woods. the plot is absurd, much more in the tradition of adventure games like sam and max hit the road and day of the tentacle than the magical realism of gabriel garcía márquez or the southern gothic modernism of william faulkner that kentucky route zero drew on. this debt the game owes to genre classics extends beyond its plot construction to its design: norco is a game that is happy to grind its pacing to a halt to have you figure out a weird puzzle.

most of these puzzles are not particularly onerous. the first puzzle in the game involves going to the gas station to buy a fuse to repair your mom’s motorcycle. the dude who used to work at the gas station has been automated out of a job, and wants you to bring him some of the pills he buys from your brother if you want to cross his picket line. alternatively, you can engage in the game’s bizarre combat system. the combat is roughly jrpg-esque. you can have each of your party members can attack in turn, and the enemies also take turns to attack. kay’s combat is a small minigame akin to simon, while every other party member’s combat minigame plays more like osu!. the implementation of the combat is rough and ready. it’s clear that combat was not the focus of the developers, as there’s only four or five actual combat encounters in the entire game. this raises the question as to why the combat is there at all. this is one of the ways in which the game is most reminiscient of snatcher. snatcher also featured about four instances where you’d have to do an awkward combat minigame that was clearly not the main focus of the developer’s time and energy.

the second puzzle in the game is one where, as catherine, you have to get into a locked building. the way you do this is by learning the secret knock from a guy selling hot dogs outside the store. the way you learn the secret knock is by getting someone to buy the guy’s hot dogs. you do this by watching a puppet show underneath the highway (which includes this game’s second most obnoxious boat minigame). then you tell the hungry stagehand that there’s someone selling hot dogs down the street. neither of these puzzles is particularly difficult, even the obnoxious boat minigame is more obnoxious in that it feels janky and unfinished more than it actually takes up your time. but these transactional adventure game puzzles feel out of place in a game that is otherwise very dedicated to gritty, realistic characterization and heightened poetic language.

the puzzles don’t serve much of a characterization purpose, because their adventure-game-y nature serves only to pull you out of the experience. they also don’t serve the textural purpose of the puzzles in kentucky route zero or night in the woods because they aren’t implemented very well. many of the game’s puzzles feel like they were meant to be more complicated, but cut back because the developers realized that they got in the way of the story.

the only way in which snatcher (specifically the sega CD version of snatcher) is still superior to norco is visual. norco’s art direction is incredible, but it suffers under the weight of bad tech art. the user interface is much higher resolution than the game art, and several fonts are provided, all of which clash with the game’s aesthetic. even the pixel font the game has doesn’t align with the pixel grid. the game also makes use of animations and effects that break the pixel grid. solving these problems is non-trivial. but for a game that clearly focuses so much on its visuals, it’s disappointing that there was not more discipline on the part of the tech team to make the art shine as well as it could have.

when the game isn’t wasting your time with awful combat and tedious puzzles, norco is an absolute joy to play. all the characters are interesting and multifaceted, and the setting is brilliantly imagined and conveyed. the game jumps back and forth between different tones, but it never comes across as having a tone problem. its juxtaposition of abstract, heightened poetic language with coarse and gritty noir characterizations and wacky adventure game plot twists feel like they capture something. norco is a product of a world in which the dominant news story of the past year has been about money laundering committed via pictures of cartoon apes; a world in which the president of the united states retweeted memes featuring a cartoon frog who peed with his pants pulled down all the way to his ankles because it “feels good, man;” a world in which there is no more line between what is serious and what is frivolous, everything is both, always, all at once.

norco contains a scene in which an oil executive driven to the brink of madness by a search for a possibly nonexistent object of unknown provenance shoots herself in front of you. norco also contains a scene in which a teenager who is a member of a cult which requires all its members to go by the name “garrett,” says that he’s been “doing the same stuff as always. ripping on that bong like it’s my job. watching hentai with the boys. putting back some cherry bang pow soda.” norco contains affecting depictions of the lives of characters near death, real harrowing moments where you confront the frailness of the human body. norco also has a private investigator who tells you that “you got to have a clean ass to fight crime.” norco concerns itself with the relationship between technology and capital, the way large companies replace what were once the functions of the government, and the way in which this phenomenon isn’t new at all: it’s just like the old company towns. norco also features an out-of-nowhere “boss fight” with a character foreshadowed exactly once who never appears again who declares “they can’t decomission me. they’ll never decomission the drone priest, baby.”

and i don’t even know what to make of the ending. norco draws extensively on biblical language and imagery, nowhere moreso than in its final moments. in this way it reminds me of dropsy. but while that game’s ending presented a clear and rather optimistic statement about what jay tholen thinks that it means to follow in the path of christ, norco’s ending is vastly more ambiguous and pessimistic. the achievement you unlock for beating the game has “:(” in its name.

norco is righteously mad about a lot of things. norco is pissed off about gentrification, about outsiders coming to the south to try and leach some of its “authenticity.” there’s a scene early on where you can meet a film director shooting a crime drama set in louisiana, and he asks you for some “local slang.” he asks you what you might call a real villanous type, and you are given three options: the real answer (“asshole”), a fake but believable answer (“bad daddy”), and an absurd answer (“crawfish… devil?”). if you give him the fake, believable answers to his questions, he reacts as you might expect: “this is how real people speak […] it’s how people talk outside silver lake, you understand?”

in a later section, catherine can observe that they turned a local hospital into “art lofts,” which she thinks is “disgusting.” while walking around the french quarter, you can overhear a group of tourists getting scammed by a fake tour guide. after the artsy puppet show sequence, you can return to the highway overpass and speak to a homeless woman who wishes the people who do those puppet shows would stop, because they draw the attention of the police. in kay’s bedroom at the beginning of the game, you can read an excerpt from a book about “crisis LARPing,” which talks about people flocking to new orleans after hurricane katrina to “help” with the disaster relief effort in a way that only served their own egos.

norco is also pissed about the conditions of the real world norco, here depicted as the relationship between norco and shield. norco returns often to the idea of the fenceline community there as an extension of sharecropping and slavery. both the in-game shield refinery and the real world shell refinery were built on disused plantation land. kay’s father died in an explosion when she was a child, and that explosion is a fictionalized version of the real 1988 shell plant explosion. that was only one of two explosions related to the refinery. the other is also fictionalized in the game, an incident in which a teenager mowing someone’s lawn created a spark which ignited fumes leaking from an oil pipeline. both he and the woman who owned the house died.

norco is also the most refreshing take on cyberpunk i have seen in years. the game’s director, yuts, doesn’t consider the game cyberpunk, but i’m not interested in what artists have to say about their own work. while yuts decries “-punk” labels as “advertising” and says “i’m not even interested in trying to construct some kind of outward facing identity that seems subversive or something,” but of course rejecting labels people try to apply to your work is just as much an act of “subversive” advertising as trying to come up with your own quirky labels. presenting your work as “unclassifiable” is also a cynical marketing tactic, one that obfuscates the fact that you’re marketing at all. norco is not unique, though i agree that the main comparison point people have jumped to, kentucky route zero, is surface level. i’ve already brought up the game’s design similarities to snatcher, but what i immediately thought of while playing norco was yussef cole’s 2018 essay hood cyberpunk:

When I think of Hood Cyberpunk, I think of visiting my grandmother’s apartment in Co-op City. Constructed on slowly settling marshland, a dozen miles away from New York’s bustling core, Co-op City is a major experimental building project in the Bronx, one of the few of its kind, and remains the largest cooperative housing development in the world. Massive, brutalist, concrete high-rises dot the landscape, looming over rectilinear, identically designed and largely vacant, strip malls and parking lots. Thanksgivings at my grandmother’s found us all cramped inside her tiny apartment dozens of stories above the ground. Wind howling in off the Long Island sound would buffet windows crammed with satellite dishes and drying laundry. One of the three televisions my grandmother always had on would toggle between grainy closed-circuit feeds of the building lobby and the laundry room. I grew up in an apartment building too, but Co-op City, like many government-funded housing projects built to house the poor, feels like a signpost leading to a one-time valorized, but now aborted future.

norco at times feels like yussef cole’s dream of hood cyberpunk brought to life. norco is quite a distance from co-op city, both geographically and spiritually. absent are the enormous tower blocks, in their place are endless deteriorating single-family homes. gone are the skyscrapers of manhattan just a short subway ride to the south, instead the flaring smokestacks of the shield oil refinery loom over norco. but the soul is here; norco is about, as yussef wrote, “people who are today experiencing the kinds of authoritarian intrusion, the hyper-policing, the corporate dominance that make up the settings of future dystopias dreamed up by well-off white people.”

the people of norco go to work at a refinery where they’re surveilled by robots armed with machine guns. they shop at stores where the omnipresent artificial intelligence that runs the cash register can tell whenever you’ve picked up merchandise and will vaporize you if you try to leave without paying.

earlier this year i read and loved william gibson’s 2003 novel pattern recognition. pattern recognition is whatever the opposite of “hood cyberpunk” is. it is a window into the reality of the cyberpunk future, infinitely more sterile than gibson and his contemporaries could have imagined in the 1980s. pattern recognition is a look into the world of terrifying wealth in the 21st century, a look into the way all radical movements will be absorbed into the body of capital and repurposed to serve its ends.

norco is an attempt to create something so unpleasant capital cannot absorb it. norco is a story about dirtbags and lowlifes. it is a story about private detectives who spend all their time day drinking at dive bars and lying about their exploits, teens who look at hentai on 4chan while taking bong hits and screaming slurs at grand theft auto online, guys who dress up like santa claus to pretend to solicit donations on the street. norco offers no escape from this life, because it knows there isn’t any.

and about those teens who love weed and hentai: they’re really who this story is about, in a way. they’re members of a cult run by a guy named kenner john, who got an audience of fashy teenage boys by posting videos online with his interpretation of the bible. he created an ARG app you can use on your phone to find these pieces of his “apocryphon” scattered around new orleans as part of initiation to his cult. the first apocryphon sets out who these people are prety clearly:

You make a few jokes, someone calls you a nazi. You throw the first punch. Things spiral out of control.

You’re outside bleeding, pushing someone’s face into a trash can full of go cups and beer bottles. The scum are screaming at you to stop but you don’t.

kenner john is a hyper-local, hyper-religious version of steven crowder, or ben shapiro, or paul joseph watson, or joe rogan, or any number of dumb fucks on the internet who make their bread and butter appealing to angry young white men who think being told to shut up is a hate crime. the “scum” are the leftist punks who frequent the gentrifying hipster bars and care about things like trying to not be racist.

norco is not willing to let either of these groups of people of the hook. the garretts are, obviously, stupid racist larpers. but they aren’t rendered faceless, and the game has a significant amount of sympathy for them. the garretts feel the walls of opportunity closing in on them like everyone else does, but they’ve been told their whole lives that they’re special.

the “scum” aren’t scum, of course, but they are mostly white mostly well-off people who to a certain extent value “virtue signalling” over actual action. in mark fisher’s essay exiting the vampire’s castle, he describes a certain subset of these people as “neo-anarchists”:

They are also overwhelmingly young: in their twenties or at most their early thirties, and what informs the neo-anarchist position is a narrow historical horizon. Neo-anarchists have experienced nothing but capitalist realism. By the time the neo-anarchists had come to political consciousness – and many of them have come to political consciousness remarkably recently, given the level of bullish swagger they sometimes display – the Labour Party had become a Blairite shell, implementing neo-liberalism with a small dose of social justice on the side. But the problem with neo-anarchism is that it unthinkingly reflects this historical moment rather than offering any escape from it. It forgets, or perhaps is genuinely unaware of, the Labour Party’s role in nationalising major industries and utilities or founding the National Health Service. Neo-anarchists will assert that ‘parliamentary politics never changed anything’, or the ‘Labour Party was always useless’ while attending protests about the NHS, or retweeting complaints about the dismantling of what remains of the welfare state. There’s a strange implicit rule here: it’s OK to protest against what parliament has done, but it’s not alright to enter into parliament or the mass media to attempt to engineer change from there. Mainstream media is to be disdained, but BBC Question Time is to be watched and moaned about on Twitter. Purism shades into fatalism; better not to be in any way tainted by the corruption of the mainstream, better to uselessly ‘resist’ than to risk getting your hands dirty.

exiting the vampire’s castle was written in 2013, quite a while before contemporary concerns about “cancel culture” arose, and it remains the most thoughtful examination of the phenomenon i’ve yet seen. it is a challenge to talk about these sorts of issues, because when you give fascists and inch they’ll take a mile. what i think both fisher and norco miss in their analysis of this issue is that they ignore this practical reason for “cancel culture.” the garretts aren’t all nazis, but some of them are. and the ones that aren’t are certainly open to the pipeline of nazification. and expecting the marginalized to infinitely tolerate endless potentially well-meaning attacks on their very existence is, to put it mildly, a bit of a tall ask. we live in an environment of constant fear, fear of being labeled as monsters ourselves, and fear that those we once trusted will reveal themselves to be monsters.

norco’s biggest narrative failing is centering its narrative of poverty and exploitation around the salvation of privileged white kids. the game includes myriad black characters, including the player character, but they are rendered largely pawns and side characters in the story of white teenagers trying to build a rocket ship to meet god.

the biggest difference norco sees between its “scum” and the garretts is laid out in the final moments of the game by a few of the “scum”:

EARRINGS: They’re not nazis.

WEIRD HAT: Yeah, they’re not nazis. They’re just impressionable dorks.

EARRINGS: They squatted a mall and built a rocket. What have we done besides drink at Saint Somewhere’s every night?

this is a real distinction that exists between the right and the left in the US. the right gets things done. the things they get done are moronic, they’re counterproductive, they make life worse for everyone on earth, but they get them done. the left can’t do anything at all.

i’ve seen many writers struggle to write about climate change, late capitalism, encroaching fascism, and related issues because of the necessity of hope. writing a piece just about how fucked we are is depressing. readers and writers want a lesson at the end, something you can take away and know what you can do to help. increasingly it feels like everything you might do is better for your own ego than it is for the world. you don’t join a protest movement, start composting, take public transit to work, call your representatives, start a garden on your balcony, stop shopping on amazon, or volunteer at a soup kitchen because it will help anyone. you do it because working towards something is a distraction from the yawning void at the center of existence. we live in the cool zone now. only time will tell where we end up.

this is the overwhelming feeling i get from norco, the feeling of the walls closing in. the feeling that there is no light at the end of the tunnel, there is no hope. kentucky route zero ended with the calm after the storm, with mourning what has lost and the hope of rebuilding in the future, all of us, together. norco ends with the only escape it can see: death.

is that good? i don’t know. it captures the way a lot of people feel right now, the way i feel a lot of the time. norco is staring into the void, held back only by when it feels the need to remind you that you’re playing a video game. norco pushes the boundaries of adventure games, strains against the cage it has put itself in. norco cannot see a world in which anything ever gets any better. it just gets worse and worse until you die.